Plague emerges from Stone Age graves

Plague may have played a pivotal role in the displacement of much of the Stone Age farming population in Scandinavia and Northwestern Europe around 5,000 years ago – a population that ultimately disappeared entirely within a relatively short period of time.

By Henrik Larsen

Plague may have played a pivotal role in the displacement of much of the Stone Age farming population in Scandinavia and Northwestern Europe around 5,000 years ago – a population that ultimately disappeared entirely within a relatively short period of time.

These findings have been published in Nature, one of the world’s most important scientific journals. The article was written by an international team of researchers headed by experts in ancient DNA from the Lundbeck Foundation Geogenetics Centre at Globe Institute, University of Copenhagen.

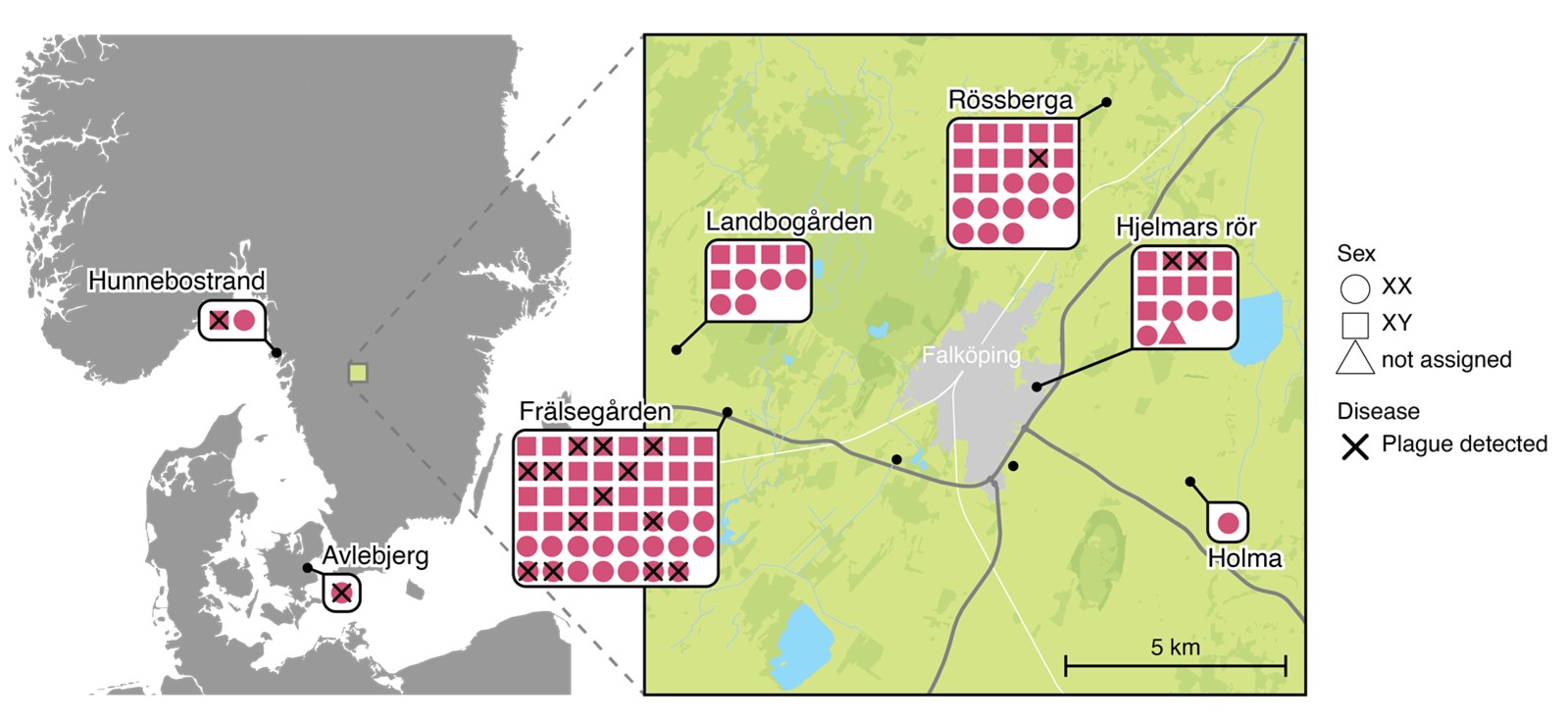

It is based on analyses of skeletal and dental remains from a total of 108 individuals who died around 5,000 years ago and who were buried in ancient passage graves made of large stones covered by earthen mounds. Much of the bone and tooth material stems from Falbygden in Västergötland, Sweden, while one of the finds analysed came from a stone cist – an ancient underground burial site not marked by a mound – in Stevns, Denmark.

“The analyses show that 18 of these individuals – 17 per cent – were infected with plague when they died. And in four of the cases, there was enough disease DNA to allow us to reconstruct the complete genome of the plague bacterium Yersinia pestis,” explains Frederik Seersholm, postdoctoral fellow at Lundbeck Foundation Geogenetics Centre. He led the DNA analyses of the ancient bone and tooth material, which were excavated and archaeologically recorded for the most part by experts associated with the University of Gothenburg in Sweden.

“Our DNA data show that the latest of the three versions of plague we identified most likely had the potential to spread among humans – and could also have developed into an epidemic. This version of plague may have been a major contributing factor to the population decline that took place in the Neolithic around 5,000 years ago when much of the farming population in Scandinavia and Northwestern Europe disappeared in the space of a few centuries. We can’t prove that this was exactly what transpired – yet. But the mere fact that we can now demonstrate that it could have happened this way is extremely significant. The cause of this population decline, known to archaeological science for quite a long time, has been the subject of intense debate, and both war and infectious disease outbreaks – such as plague – have been considered. In the case of plague, there have been several theories, one being that plague could not have reached epidemic proportions during that time period – but there’s no evidence to support that anymore,” says Seersholm.

POWERFUL TECHNOLOGY PROVIDED ANSWERS

The DNA analyses behind the Nature article were conducted using a special technique called Deep Shotgun Sequencing, which can extract extremely detailed information from archaeological DNA – even genetic material so ancient that it would typically be heavily degraded.

Thus, in addition to the plague analyses, the team behind the Nature article has also been able to determine the blood relationship between 38 individuals from Falbygden, 12 of whom were infected with plague when they died. The team was also able to chart the family tree of those 38 individuals over a period of 120 years – across six generations – providing a new understanding of the family structures in that part of Scandinavia at that time. Genetic analysis revealed, among other things, that the men in this family often had children by several women, while the women appeared to be monogamous.

Together, these findings show how much can be achieved with Deep Shotgun Sequencing,” says one co-author of the Nature article Martin Sikora, associate professor at Lundbeck Foundation Geogenetics Centre and expert in populations genomics:

“We successfully conducted extensive sequencing of plague lineages, and we also delved deep into the microbial components of the DNA. At the same time, these analyses have enabled us to move from an overall to a local perspective – and gain insights at an individual level into the social organisation that existed at the time,” explains Sikora.

MORE ANCIENT BURIAL SITES AWAIT

One of the key findings presented in the Nature article is that

The identification of plague in 17 per cent of the 108 individuals via DNA analysis of skeletal and dental material enabled the international team of researchers “to demonstrate with certainty that plague infection was not a rare occurrence in Neolithic Scandinavia”.

Regarding the investigation of the Swedish finds from Falbygden, the Nature article shows that the family of 38 individuals suffered at least three outbreaks of plague in the six generations the researchers were able to map.

“The matter of the blood relationship between the individuals whose bone and teeth were found in the passage graves has been debated for at least 200 years. There have been many theories and suppositions, but now, thanks to DNA, there is concrete data,” says Karl-Göran Sjögren, researcher in archaeology at the University of Gothenburg and another co-author of the Nature article.

These data have resulted in several interesting finds, explains Sjögren: “In one of the burial sites in Falbygden, for example, we found that one group of individuals were buried in the northern end, while another group lay in the southern end. DNA analysis showed that they were two separate families. But analysis also revealed kinship, even if somewhat distant, between the two groups.”

One of the complete skeletons found in the Frälsegården passage grave. Photo credit: Karl-Göran Sjögren.

The blood ties in the Swedish burial sites identified via DNA analysis also tell us that this Scandinavian culture appears to have practised female exogamy. That is, that women who were to carry on the lineage were brought in from outside – from other groups.

“When you look at all the information that could be extracted from the skeletal and dental material from the Swedish passage graves, it makes sense to continue along this path and study specimens from the Danish burial sites,” says Anders Fischer, archaeologist. He holds a PhD and MA specialising in Stone Age cultures, is associated with the Lundbeck Foundation Geogenetics Centre and the University of Gothenburg and is also a co-author of the Nature article.

“We have hundreds of well-preserved skeletal remains from Danish prehistoric passage graves in collections across the country,” says Fischer:

“Some of the questions we hope to find answers to through DNA analysis of these skeletal remains – and comparison of the results to archaeological studies – might concern the last migration to Northwestern Europe and Scandinavia. That is, the migration that took place when much of the Stone Age farming population was displaced from this area around 5,000 years ago. Regardless of whether it was caused by plague or a combination of plague and war – because that is also a possibility.”

The people who at that time – in the case of Denmark, this would be exactly 4,850 years ago – became the de facto winners and settled permanently in Scandinavia, were a combination of herders from the Pontic Steppe and a group of Eastern European Stone Age farmers.

These Steppe people, known as the Yamnaya, came from a region spanning from parts of modern-day Ukraine across Southwestern Russia to Western Kazakhstan. The Yamnayas – who along their migration route towards Scandinavia also mixed genes with Eastern European Stone Age farmers – are the closest genetic ancestors to present-day Scandinavians. This was demonstrated by the findings of another large-scale DNA project published in Nature in January 2024.

“One of the questions we could seek to answer by DNA analysis of a large number of skeletal remains from ancient Danish passage graves is the extent to which the Yamnayas married into the local Scandinavian families. That is, whether they mixed genetically with the Neolithic farmers who remained when the Yamnayas arrived in Scandinavia.

“With the help of advanced DNA technology, we should also be able to coax an answer to that question from these skeletal remains,” concludes Fischer.